why intellectuals must raise questions

an inquisitive mind is one that is not dead. it is a sharp weapon that cuts through the vague cloud of oblivion. curiosity is life. a questioning spirit is one that takes to task the unclear and the ambiguous. to spectate without a skeptical knack is to endure a potato existence. a mind that is not curious is dead meat. for it to be alive, there has to be a constant inquisition that demands answers, that does not stop till truth is unfolded on its path. and that finally walks over the terrains of truth, and that does not stop at moments of doubt, and that rather strengthens in the dark wells of doubts, and that finally erupts out a victor. such inquisition and such an inquisitive mind alone is pure, such an inquisitive mind alone is chaste, such an inquisitive mind alone is fertile, such an inquisitive mind alone is profound, such an inquisitive mind alone is supreme.

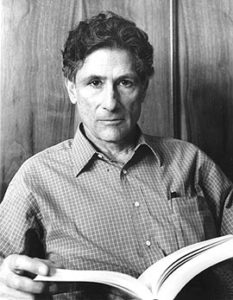

Edward Said was a renowned professor of literature at Columbia University, a public intellectual, and a founder of the academic field of postcolonial studies. an arab-american who spoke out against american foreign policy and its support for israel, said was a tireless advocate of palestinian rights.

in 1993, he presented his bbc radio 4 reith lectures on “representations of the intellectual.” said was appealing here to intellectuals – and budding intellectuals – to reflect upon their craft and political engagement. expertise, he said, goes beyond competence, of being conscientious about what you do, and having the right skills to do it. rather, said stressed the importance of making choices. he asked what was for sale, whether the goals you set yourself with your expertise were conformist or critical, and, perhaps most importantly, in whose interests were you acting?

“the particular threat to the intellectual today,” said reckoned, “is an attitude i call professionalism.” professionalism “means thinking of your work as an intellectual as something you do for a living, with one eye on the clock, and another cocked at what is considered to be proper, professional behaviour – not rocking the boat, not straying outside the accepted paradigms or limits, making yourself marketable and above all presentable.”

all of which can, and indeed should, be countered by courageous intellectual amateurism. anybody can do it – even professionals. above all, it means a readiness to withstand comfortable and lucrative conformity, a desire “to be moved not by profit or reward but by love for and unquenchable interest in the larger picture, in making connections across lines and barriers, in refusing to be tied down to a specialty, in caring for ideas and values in spite of the restrictions of a profession.”

an intellectual ought to be someone who raises questions at the very heart of professionalised activity. it’s a sense of self-worth, said reckons, an affirmation of engaged activity that hinges on an audience. indeed, is that audience there to be satisfied, a client to be kept happy? or is it there to be challenged, provoked, mobilised into collective, democratic action?

source: versobooks.com

http://www.versobooks.com/blogs/